Testing of CUBA applications

Part 1 - Introduction to Test automation

One of the main parts of today’s application development that is not very prominent in CUBA applications is automated testing. This is the reason we’ll take a deep look into this topic in this blog post.

The story about automated testing

Automated testing of software has a pretty long history. Since there is a general need to know if a certain program does what it is supposed to do, the producer of the program might either test the result manually or through another program that does the job.

Programmers are normally lazy since this is the very nature of their craft and the results of their craft are things that enable other people to be lazy as well (we normally call these programs “productivity tools” but they could also be regarded as “laziness tools”), it is not a big surprise that doing manual testing of the resulting program is not a very good fit.

The problem of ensuring that the resulting program does its job right can be tackled from two different angles.

The first is to delegate this task to other persons. This approach has been done very successfully (at least for the programmers) for quite a long time. QA teams evolved next to the dev teams and the over-the-wall syndrome was cultivated just like with the operations people.

The second approach is to leave the responsibility for QA at the developers. This leads (since the above described laziness) to automation of this task.

This is obviously a highly oversimplified description of the situation and therefore should be treated with a ;)

Because the first approach has quite a few downsides, we’ll take a closer look at the second approach to the problem: How can we test the software we wrote in an automated fashion?

General ways of testing

When we look at general options on how to test a software in an automated fashion, normally there are different kinds of testing. One dimension is the granularity of the test and the system under test (SUT).

Starting with unit testing, which is the testing style with the smallest scope. In a unit test, a unit is tested in isolation. In an object oriented language a unit oftentimes means a class, but this one-to-one mapping is not necessary. It could be a method or a package as well, depending on your definition of a “unit”, but for now we can stick to the “unit = class” mapping. In order to test a unit in isolation, it is required to cut off the dependent units. This is normally done through a technique called Mocking or Stubbing.

The next granularity step would be an integration test. In an integration a unit is not tested in isolation anymore, but instead different units are combined together. The resulting system of the different units are tested in conjunction. Multiple units can be something like multiple spring beans or classes, but it can also mean the database access code in the application server together with a real database.

In comparison to a unit test, where the dependencies are stubbed out, for integration tests the real dependent units are used. This normally leads to a more “real” test scenario. On the other hand, it will make a test slower and more brittle, because of more moving parts that are involved. Additionally it makes it a bit harder to reason about, because if a test shows that a certain feature does not work, it is harder to break down the problem to the actual unit with the bug.

On the other end of the spectrum of granularity there would be something like a functional test. Functional tests (sometimes called “system tests”, “UI tests” or “end-to-end tests”) normally differ from the first two options in that as they treat the system under test as a black box, meaning that there is no need of information about internal structures of the system in order to setup or execute the test.

Such test treats a system as it is, meaning that it normally uses the exposed interface to interact with it. This means that a system has to be up and running completely as well as potential dependent systems. As the size of the system under test increases, the setup costs as well as the brittleness of the test execution increase as well. On the other hand, a succeeding functional test gives you much higher level of confidence compared to a unit test.

Orthogonal testing dimensions

Although the granularity dimension for classifying tests is the most relevant, there are some other aspects that don’t really fit into this category. I’ll name a few of them but will not go into further details about it:

Acceptance / behavior tests differ in the sense that they look at the topic from the users angle. Oftentimes, acceptance tests are directly related to a user story in the agile world. Nevertheless, an acceptance test can be implemented as a functional API test as well as a unit test.

Load tests are an example of tests that target the goals of non-functional requirements. Security tests are the same in this sense. Oftentimes security tests are only automated to a certain degree, because it requires more creativity of the tester, just like exploratory functional testing.

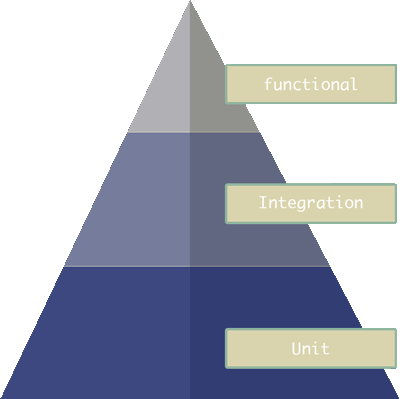

Testing pyramid

Getting back to the granularity dimension, something that is very prominent in the testing space is the testing pyramid. This analogy is used to express the amount of tests that each category should contain. More precisely, it expresses a reasonable ratio between the amount of unit / integration / functional tests.

As described above, functional tests are generally slower to write & execute, harder to maintain, more brittle but more realistic and meaningful. Unit tests are fast, easy to write and setup but less realistic.

Therefore a realistic ratio is very advisable. More information about the test pyramid and the impact can be found at the description from Mike Cohn or at the de facto standard software blog.

TDD

Another topic is the question about when to write a test. Test driven development aka TDD is a pretty straightforward technique that shifts the test creation before the actual implementation. This way the implementation flows naturally alongside your test cases that will drive the design of the API of the unit. Test driven development has its roots in the early extreme programming days and is already around for about fifteen years.

I won’t go into much more detail on this topic, as this is a complete blog post on itself. Also there is a lot of information already out there about this topic. As a starting point you can look at “the” TDD book by the inventor himself. But as always, TDD is not a silver bullet. There are some negative thoughts on it in the community as well lately like the famous “TDD is dead” article by the Rails creator DHH.

Let’s leave this pretty general and theoretical topic for now and have a look at some basic examples to get into this testing thing a little bit more…

How to do unit testing

So let’s have a look on how to do unit testing in general. As I said before, the point of a unit test is to test a particular unit (let’s assume a class) in isolation. The reason is, that we want to control the external world of this object in order to check certain behavior with eliminating the possibility that any other external situation of the environment is causing the expected result or interferes with our unit under test. This allows us, just like in a lot of other science experiments, to “proove” a certain behavior of our code.

Here’s the basic example that we will use for now (actually it is from my original groovy blog post).

class Customer {

String firstName

String lastName

List<Order> orders = []

boolean isGoodCustomer() {

orders.size() > 0

}

}

class Order {

int amount

}We have a customer class that has a firstName and a lastName. Additionally it has a list of orders that have been placed by this customer. Next to the data, it has some behavior (like every good OO class should have). The method isGoodCustomer checks if any order has been placed by the customer and the customer therefore can be called a “good” customer.

Spock - the unit testing framework of my choice

With this business code, it is possible to write a unit test for the customer class. But how and what tool to use? Well, generally in the Java world the de-facto standard is JUnit. It’s the most dominant unit testing library in the field. But although it is a very good unit testing library, it has some downsides. One of them is, that a normal JUnit test has only a limited possibility to let the writer express the intend of the unit test. Most of these restrictions come from the Java language and some are directly related to JUnit. Since the expressiveness of a unit test is probably even more important than it is in production code, this is not a very good starting point.

Therefore I will use the spock framework as the unit testing framework of my choice for this article series.

Spock is based on groovy, which allows it to create a expressiveness for tests that is quite fascinating. It uses things like power assertions and strings as methods that will lift up the average unit test expressiveness very much. Next to this very important feature we will see other different benefits like integrated mocking down the road.

Since we are in the CUBA world for now, I created a sample cuba application: cuba-example-spock that already has the dependency to spock included as well as the following unit tests included.

In the build.gradle file of the example project, I added the spock dependency to the application like this:

configure([globalModule, coreModule, guiModule, webModule]) {

// ...

dependencies {

testCompile('junit:junit:4.12')

testCompile('org.spockframework:spock-core:1.0-groovy-2.4')

testRuntime('cglib:cglib-nodep:3.1')

}

// ...

}Additionally you have to configure the application with groovy support through CUBA studio. Alternatively you have to adjust you build.gradle like this:

configure([globalModule, coreModule, guiModule, webModule]) {

apply(plugin: 'groovy')

sourceSets {

main { groovy { srcDirs = ["src"] } }

test { groovy { srcDirs = ["test"] } }

}

}With this setup, spock is able to run and execute our unit tests.

Since it is a gradle project the tests can be executed via gradle like this in the root of the project directory:

./gradlew checkIf you are using IDEA as your IDE and have imported the project as a gradle project, you can also use the IDE integration (like STRG + SHIFT + F10 for running a particular test class)

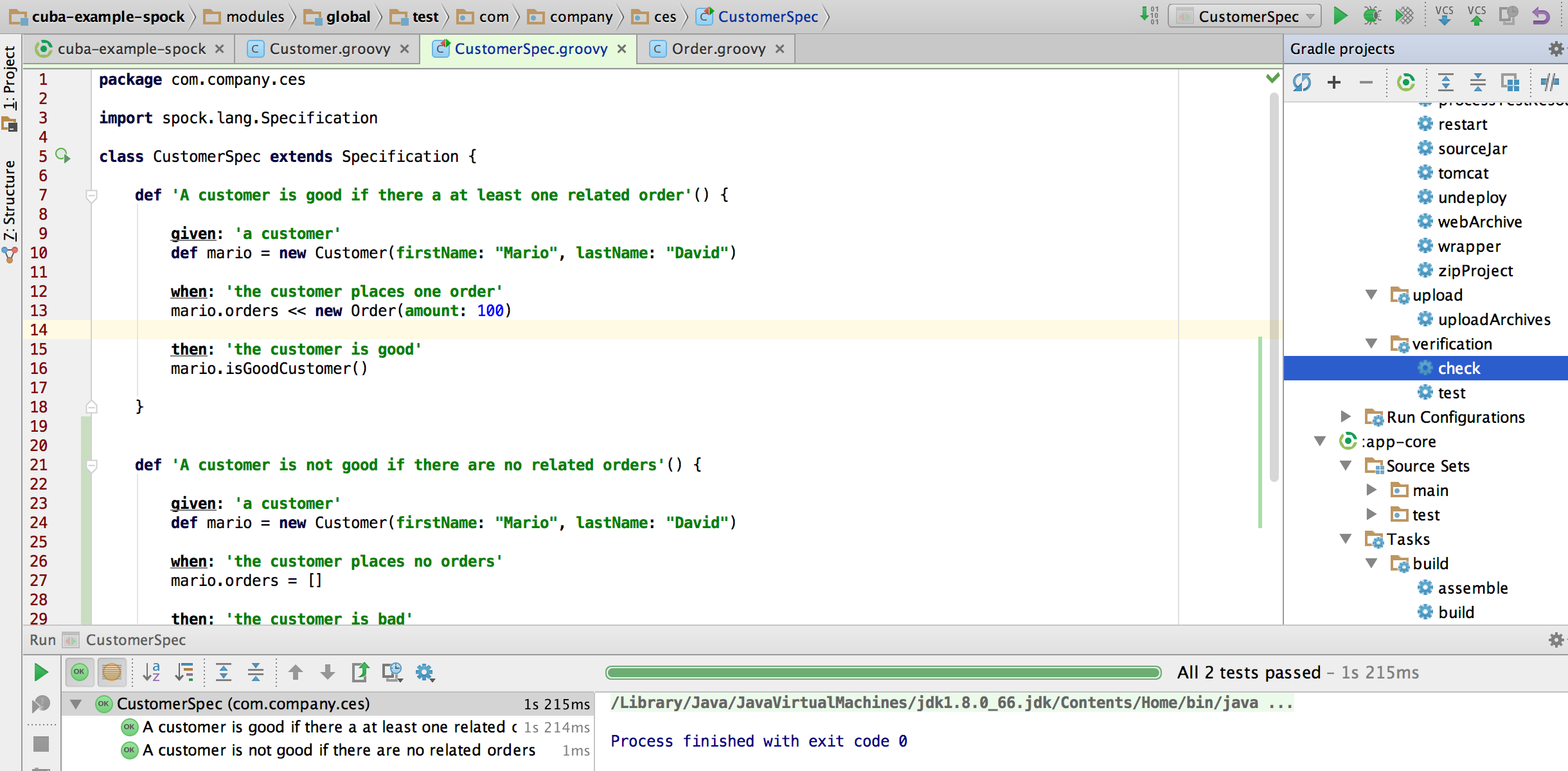

Creating our first unit test

So this is the time, we create our first unit test. Let’s get back to the Customer class I’ve shown you earlier. When we think of a possible path through the code, the most obvious one is what is often called the “happy path”. This means that we write a test that will check if the positive situation of the code that we want to test is executed correctly. In our case, where we want to unit test the isGoodCustomer method of the customer class, this would be:

- A customer is good if there is at least one related order

So let’s try to implement this behavior. First we have to create a Customer and further setup the system under test (the user). The next thing is that we actually execute the method we want to check. After that we check the outcome of the execution. This pattern is called AAA (Arrange Act Assert) and is fairly common in the testing space.

Spock has some keywords for the AAA pattern, called “given”, “when” and “then”. These can be used together with a comment as you can see below. This is very useful because it describes the code within the block that is sometimes a little bit complicated when using mocks etc.

So here’s the first test case:

def 'A customer is good if there a at least one related order'() {

given: 'a customer'

def mario = new Customer(firstName: "Mario", lastName: "David")

and: 'the customer places one order'

mario.orders << new Order(amount: 100)

when: 'we want to know if the mario is a good customer'

boolean isMarioGoodCustomer = mario.isGoodCustomer()

then: 'mario is a good customer'

isMarioGoodCustomer == true

} For the happy path test, we have to create a customer instance. Next we add an Order to the orders bucket of the customer. After that, we call the method isGoodCustomer and store the outcome. In the last section we check if “mario” really is a good customer. After executing this test, we will see that the happy path is implemented correctly.

So, to determine the next test case there is a technique called equivalence partitioning. When you think about what inputs can be passed into the test case (in the orders list in this case), there are different options. The orders list could be filled with zero orders, with one order, with three orders, or fifteen orders. Then it could be more edge based cases like empty list, null, list with a null element. Since the class is groovy this my case, orders could be a String.

I’ll not go into much detail about this topic, but it basically means, that we can treat different similar inputs like the same, e.g. 5, 8 and 14 elements, because we know that this will not make a significant difference. Therefore one test with multiple elements will probably be enough. Instead we should make different classes of inputs that are different. Therefore let’s look at the “normal” negative case where:

- A customer is not good if there are no related orders

Here’s the corresponding test.

def 'A customer is not good if there are no related orders'() {

given: 'a customer'

def mario = new Customer(firstName: "Mario", lastName: "David")

and: 'the customer places no orders'

mario.orders = []

expect: 'the customer is bad'

!mario.isGoodCustomer()

} Note, that I used the combination of “given” and “expect”, instead of “given”, “when”, “then”. This is mostly a different style regarding the documentation of the test case. I use it from time to time when I test a method with a boolean return value that can be evaluated in place. Spocks power assertions allows us to write the last line like this !mario.isGoodCustomer() and forget about the assert keyword. For more information about power assertions, you can have a look at this blog post Spocklight: Assert magic.

So here’s the fully fletched unit test.

class CustomerSpec extends Specification {

Customer mario

def setup() {

mario = new Customer(firstName: "Mario", lastName: "David")

}

def 'A customer is good if there a at least one related order'() {

given: 'the customer places one order'

mario.orders << new Order(amount: 100)

expect: 'the customer is a good customer'

mario.isGoodCustomer()

}

def 'A customer is not good if there are no related orders'() {

given: 'the customer places no orders'

mario.orders = []

expect: 'the customer is bad'

!mario.isGoodCustomer()

}

def 'A customer is not good if the orders list is null'() {

given: 'the customer places no orders'

mario.orders = null

expect: 'the customer is bad'

!mario.isGoodCustomer()

}

}In this case, I pushed the initialization of the customer in the setup method. This method gets called before each test case is executed. Putting the common setup parts in the corresponding method normally leads to a better readability of the actual test cases.

When you execute the tests you’ll notice that the last test is not green. In this case, I set orders to null and executed the method. Unfortunately we got a NullPointerException. This situation oftentimes happens, because you encountered an edge case through different inputs that was not handled in the application code. One could argue that this is not a case that has to be caught, since the orders array is initialized already on object creation. But as the fix only requires a single character, let’s just make that happen.

This change will make the test green again:

class Customer {

// ...

boolean isGoodCustomer() {

orders?.size() > 0

}

}The null-safe operator ? will evaluate orders.size() > 0 to null instead of throwing a NullPointerException. Since it is evaluated to a boolean as the method return value requires, null is false in groovy –> the customer is not good. This is probably the behavior we want to achieve.

With this we are ready with our first unit test. Let’s look at what we already discussed and what are the next steps.

Summary and outlook

In this article we learned about test automation. Its different categories which all have their different reasons to exists. After that we looked at Spock as the testing tool and explored our first unit test with a simple class under test.

As we probably already reached the point where the last reader close the browser tab since the blog post is already too long, we will shift the interesting topics to the next blog post(s).

In the second part of the “Desert of Testing” series, we will take our CUBA glasses back on and go through the different artifacts of a common CUBA application like Entities, Services and Controllers and try to tests these. With it we will explore more testing techniques like Mocking.

In the third part, we will try different testing types in the CUBA application and try to especially look at functional testing.

I hope you have enjoyed the longish article and will get back to me with feedback or questions about this topic.